Introduction

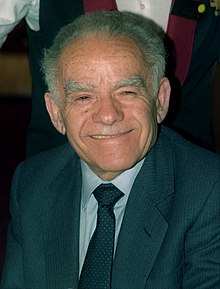

Dan Shechtman is an Israeli scientist whose discovery of quasicrystals revolutionized the field of materials science and earned him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2011. His discovery, which was initially met with skepticism and even hostility from parts of the scientific community, ultimately led to a profound shift in our understanding of crystal structures. Shechtman’s work is now considered one of the most significant contributions to chemistry in the 20th century.

Early Life and Education

Dan Shechtman was born in Tel Aviv, Israel, in 1941. He grew up in a modest household but showed great promise as a student, especially in the fields of mathematics and science. He pursued higher education at the Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, where he earned his bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering. He continued his studies at the Technion, eventually obtaining a master’s degree and a Ph.D. in materials science.

After completing his education, Shechtman took on various research positions around the world. He worked at prestigious institutions, including the National Bureau of Standards in the United States (now NIST), where he developed his expertise in electron microscopy, a tool that would later prove crucial in his discovery of quasicrystals.

The Discovery of Quasicrystals

In 1982, during a research sabbatical at Johns Hopkins University, Shechtman made the groundbreaking discovery that would change his life and the field of crystallography forever. While studying the properties of a rapidly solidified alloy of aluminum and manganese, Shechtman observed a diffraction pattern that did not conform to any known crystal structure. This pattern displayed 10-fold rotational symmetry, something that was thought to be impossible for crystals, which were believed to have only certain allowed symmetries.

Shechtman’s observation was extraordinary because it contradicted the long-held assumption that all crystals are periodic. Crystals had always been defined as materials with a repeating, regular arrangement of atoms. However, the structure that Shechtman had discovered was aperiodic, meaning that it did not repeat in a regular pattern. Despite this, the structure still maintained a well-ordered arrangement, which he called a “quasicrystal.”

When Shechtman first presented his findings, the scientific community reacted with disbelief. Many of his peers were highly skeptical, and some even ridiculed his work. Linus Pauling, one of the most famous chemists of the 20th century, was a vocal critic, famously stating, “There are no quasicrystals, just quasi-scientists.” However, Shechtman persisted in his research, confident in the validity of his discovery.

Overcoming Skepticism

For years, Shechtman continued to gather evidence and conduct experiments to support his findings. Slowly but surely, other researchers began to replicate his results, and the existence of quasicrystals was eventually accepted by the scientific community. The development of new mathematical models, particularly Penrose tilings, helped explain how quasicrystals could exist in a non-repeating yet ordered structure. By the 1990s, quasicrystals were no longer considered an anomaly but a new class of materials with unique properties.

Quasicrystals have since been found in a variety of natural and synthetic materials, and their discovery has opened up new avenues for research in materials science. They possess properties that make them useful in industries such as aerospace, electronics, and coatings, where their low friction and high wear resistance are particularly valued. The study of quasicrystals has also influenced fields as diverse as art and architecture, where their non-repeating patterns have inspired new designs.

Recognition and Nobel Prize

In 2011, nearly three decades after his initial discovery, Dan Shechtman was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work on quasicrystals. The Nobel Committee recognized his perseverance in the face of opposition and his groundbreaking contributions to science. Shechtman’s discovery had fundamentally altered the way scientists think about solid matter, and his work continues to have a lasting impact on chemistry and materials science.

Shechtman’s Nobel Prize was not only a personal triumph but also a significant moment for Israeli science, as he became the tenth Israeli Nobel laureate and one of the few to win in the field of chemistry. His success story has inspired countless young scientists in Israel and around the world to pursue research, even in the face of skepticism.

Current Work and Legacy

Even after receiving the Nobel Prize, Dan Shechtman has remained active in the scientific community. He continues to teach at the Technion and holds visiting professorships at several universities around the world. His research has expanded beyond quasicrystals, but he remains deeply engaged in the study of novel materials and their potential applications.

In addition to his scientific work, Shechtman has been an outspoken advocate for science education and entrepreneurship in Israel. He believes that fostering a culture of innovation and critical thinking is essential for the future of Israel and the world. Shechtman has also run for the presidency of Israel, though he was not elected. Nevertheless, his passion for education and scientific inquiry remains a hallmark of his career.

Learn More

For more information about Dan Shechtman and his groundbreaking discovery of quasicrystals, visit his Wikipedia page or explore further at MIFF.